Disruption for Doctors 3: the Rise of Selfcare

This is the third post of a three part series on “Disruption for Doctors” (which is nice alliteration, but really this is for anyone working in, or thinking about, healthcare):

Part I, introduced the idea of “disruption” as first defined by the late Clayton Christensen in his 1997 best-seller The Innovator’s Dilemma: the process whereby a new technology creates a new business model, allowing new companies to successfully overturn incumbents.

Part II provided specific examples of disruption within the healthcare system: from Walmart Health to IDx-DR, the first AI (artificial intelligence) system approved by the FDA to make a medical diagnosis (of diabetic retinopathy) without a doctor’s input, to Chestlink , an AI system designed to read chest x-rays.

This post focuses on even bigger disruptions to the whole healthcare system, on innovations that move things not just from a specialist to a generalist (like IDx-DR), or from a hospital clinic to a Walmart clinic, but away from providers and clinics entirely.

I refer to this as “selfcare”: the system whereby untrained consumers can perform former healthcare tasks without interacting with a “provider” like a doctor or nurse.

I’ll start with over-the-counter (OTC) medicines, a great example of disruptive selfcare that is completely under the radar of most in healthcare. Then I’ll move on to more directly IT-intensive disruptors like AI.

The IT revolution goes consumer

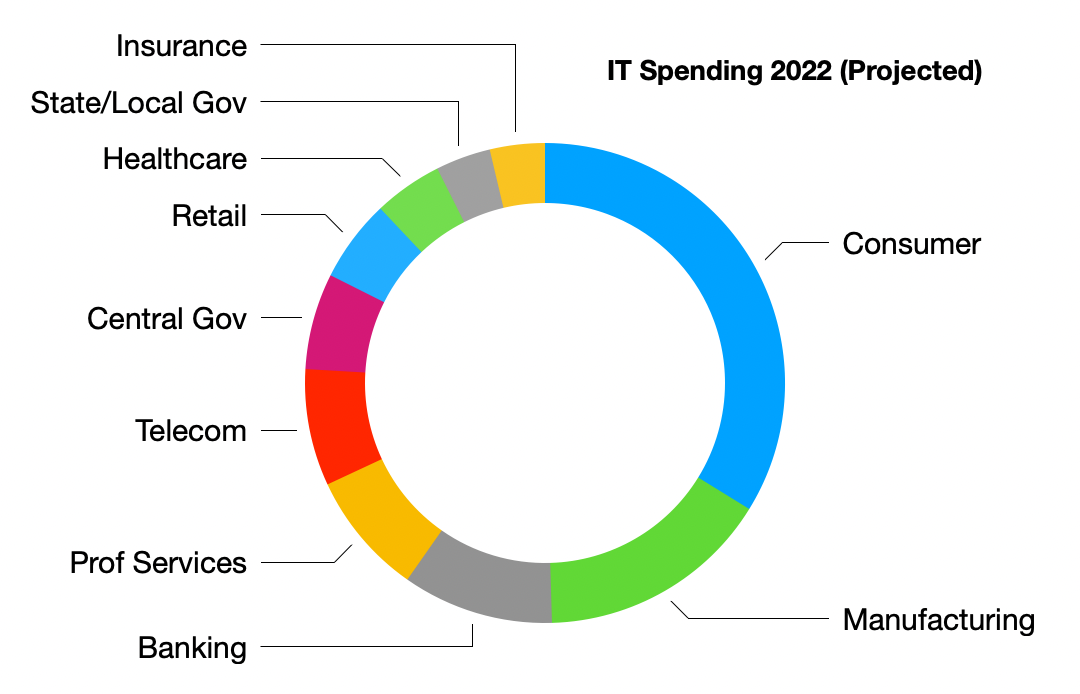

Computing has gone through three major stages over the last 100+ years, when viewed from the eye of the consumer. In the first, which reached all the way up into the 1970s, computers were so expensive and difficult to purchase and maintain that only large institutions (government, industry, universities) could be customers.

The second stage began in the 1970s with the early “personal” computers, and ran all the way through the beginning of the 21st century. In this stage, the cost (and size) of components dropped sufficiently that it was possible to begin selling computers (i.e. PCs) to much smaller institutions, including small businesses or even individuals.

The third stage, which has characterized computing in the 21st century, is the consumer stage: the biggest chunk of the worldwide market for information technology is for consumer technology, with smartphones taking the biggest piece of that chunk.

Consumer computer

Compared to the roughly $1.5 trillion projected for consumer IT spending, the portion expected for healthcare, roughly $200 billion, is small potatoes. And these numbers reflect a substantial decrease in consumer spending projected for 2022 after the huge spike in lockdown-related sales of laptops and other computers to consumers during the pandemic.

The augmented consumer

These IT spending numbers matter, because in our lifetimes the most important way that we all gain new capabilities is via IT (especially smartphones). And we’ve all gained so many new capabilities via smartphones and apps that it’s hard to keep track.

In healthcare, as reflected in its laggardly IT spending? Not so much.

The biggest IT spending in healthcare in the last ten years has been to purchase “EMRs” (electronic medical record systems), partly with $30+ billion in federal subsidies. Many hospitals systems have spent upwards of $100 million on their EMR, and the big EMR companies (like Epic and Cerner) are tremendously influential in the healthcare system.

But guess what: consumers spend more money each year on AirPods than healthcare spends each year on EMR! And because of IT, consumers have been gaining new capabilities much more rapidly than the healthcare system.

Yes, Apple makes more money just on AirPods than the biggest EMR vendors combined

This wouldn’t matter for healthcare if consumer capabilities were unrelated to healthcare capabilities. But they are very related: many of the things that IT now lets consumers are do for themselves are things that used to be “healthcare.”

You don’t need AI to replace doctors

Over the last few decades, hundreds of medicines have been moved from prescription to OTC. The FDA said in 2016 that there were more than 700 drugs that “would have required a prescription only 20 years ago” and this number has presumably grown since then. Those would include commonly used drugs like Claritin (loratadine) or Advil (ibuprofen) — hard to remember now that you used to have to visit a doctor to take Advil!

More than 700 current over-the-counter drugs would have previously required a prescription from a doctor

Part of the reason why FDA can move drugs to OTC, of course, is that consumers today have many more tools to find out medical information than thirty years ago: computers, the internet, Google, drugs.com, Medscape.com, smartphones, to name just a few. Consumers equipped with Google are much better able to educate themselves about their health.

I’ve been asked many times whether I think that AI will replace doctors. Never once have I been asked if I thought that OTC drugs could replace doctors. But that’s exactly what they have done: every time a drug switches from prescription to OTC, the total number of doctor visits drops.

In fact, a 2012 study by Booz concluded that

“if OTC medicines did not exist, an additional 56,000 medical practitioners would need to work full-time to accommodate the increase in office visits by consumers seeking prescriptions for self-treatable conditions.”

Fifty-six thousand doctors that we don’t need because of OTC drugs; that’s almost 6% of the practicing doctors in America. Think of the effect on healthcare costs.

But AI is an accelerant

If we thought that Google-equipped consumers were better able to manage their health, AI is going to blow that away. A product called ResAppHealth is a powerful example.

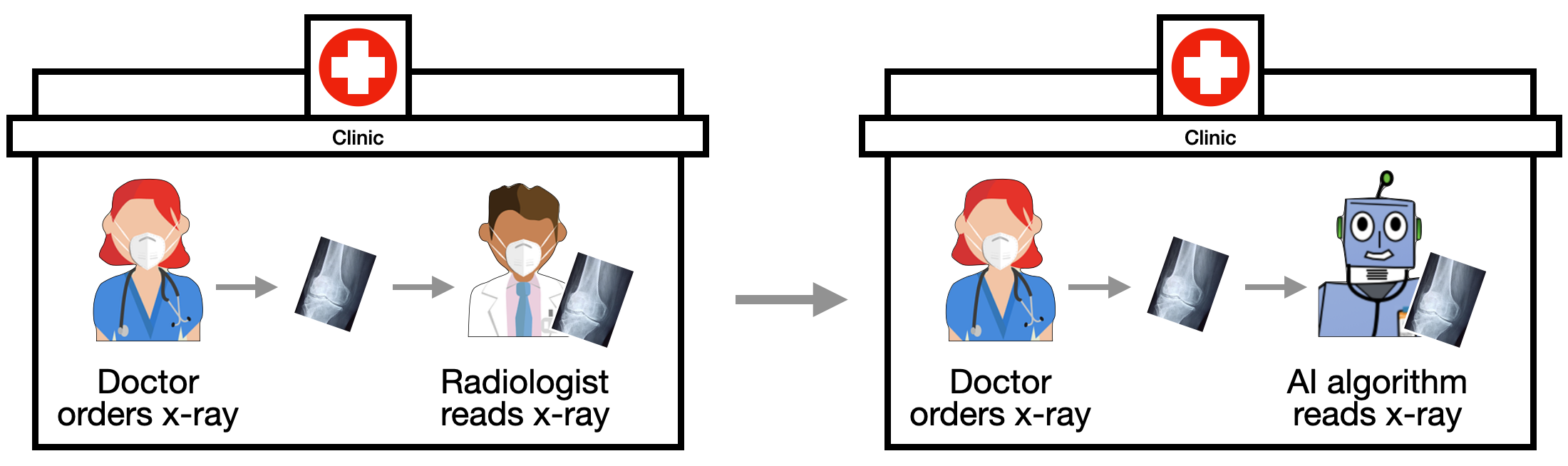

We’ve probably all heard something about the uproar in radiology concerning AI. Most of this was sparked by a 2016 comment by eminent AI researcher Geoffrey Hinton saying that new types of AI were going to be better able to read images than expert human radiologists.

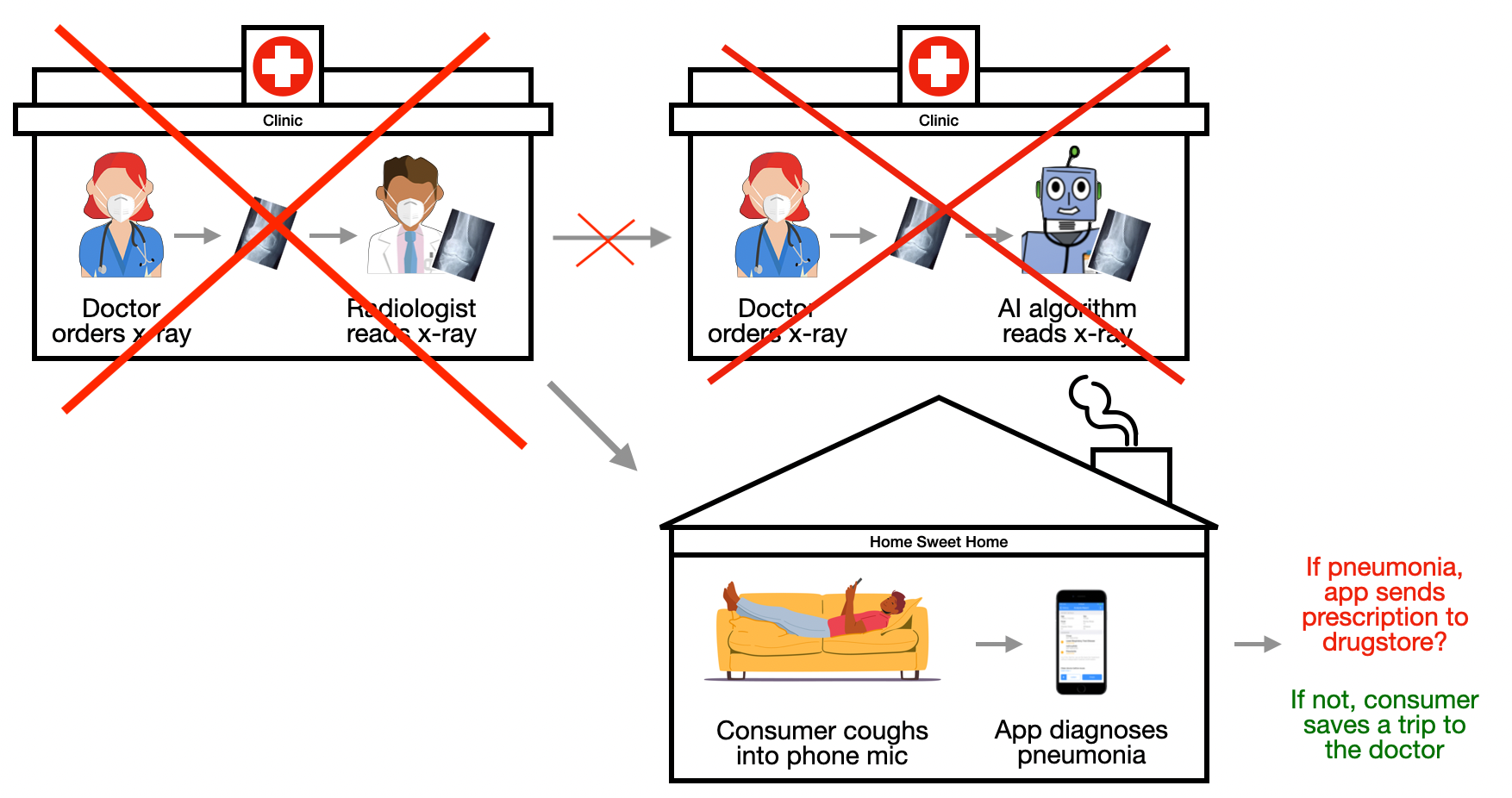

So Hinton was really describing the possible disruption within healthcare of substituting an algorithm for a radiologists but leaving the rest of healthcare intact, as in the image below:

Will AI disrupt radiologists, but leave the rest of the healthcare system intact? I don’t think so.

ResAppHealth (as of this month a subsidiary of Pfizer) gives us an idea of what Hinton missed, and how AI is more likely to disrupt the whole of healthcare, rather than just a piece here and there.

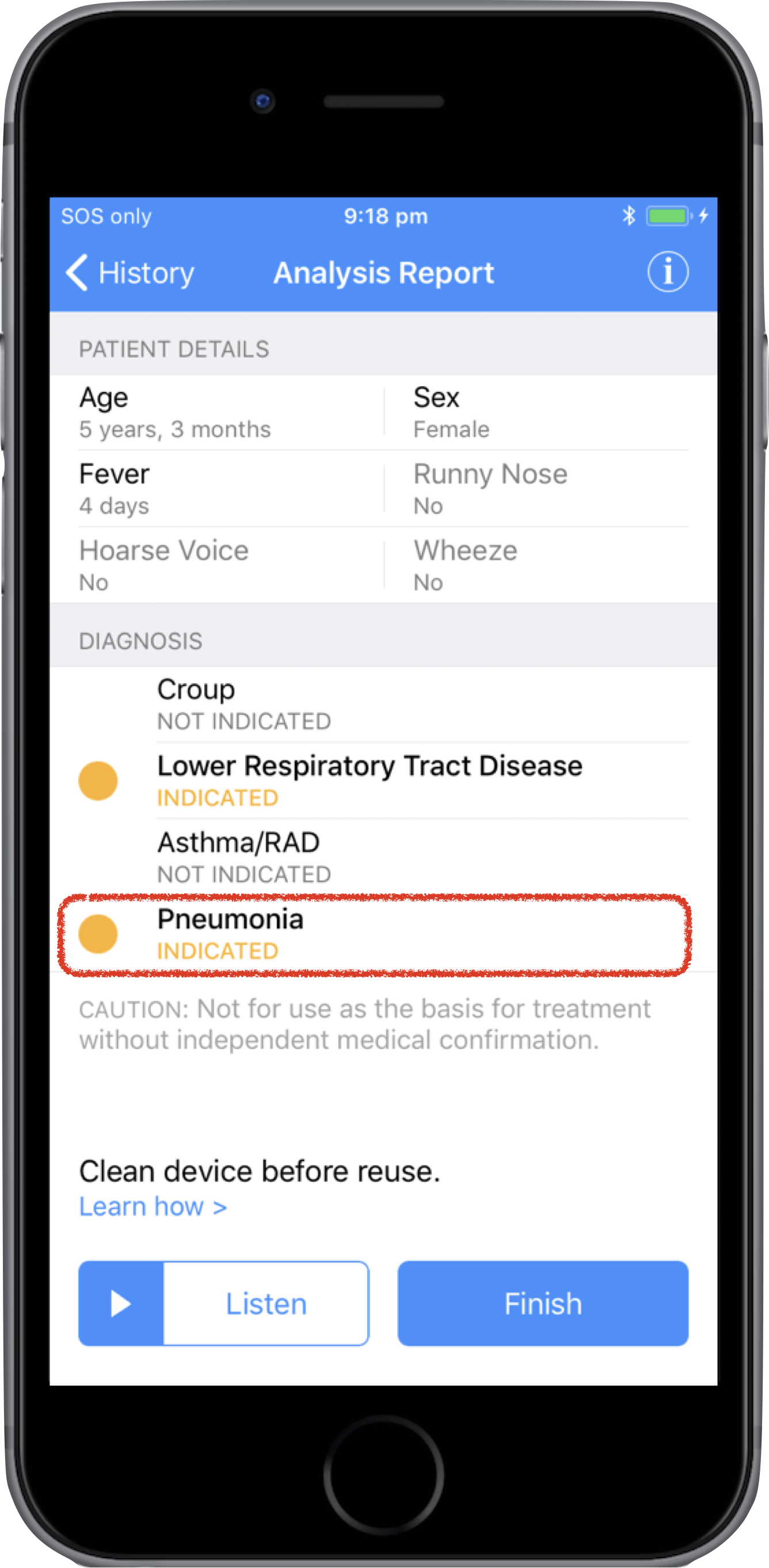

ResApp was created by Australian research physicians who thought “when I want to know if a patient has lung problems, I listen to their breathing with a stethoscope to detect any pattern characteristic of pneumonia. I wonder if we could automate that process with AI.”

So . . . now they have a smartphone app that listens to your cough and tells you if you have pneumonia. And they are marketing it to healthcare providers and directly to consumers.

Now, imagine the market for a tool that gives every person the ability to diagnose, or rule out, pneumonia (every parent on earth, for starters). And imagine how that affects healthcare:

ResAppHealth

Just as with OTC drugs, information technology gives consumers a capability they didn’t have before. And suddenly, a skill requiring 10+ years of training becomes a smartphone app. And that aspect of healthcare — reading x-rays to check for pneumonia — suddenly . . . isn’t healthcare anymore. Costs go down dramatically, more people in need of care are able to get it.

Even the in-healthcare examples I’ve provided in Part II, like IDx-DR (the AI system that diagnoses diabetic retinopathy without an ophthalmologist) are not likely to stay in-healthcare very long. Although for business (and regulatory) reasons that company is now marketing the product to primary care practices, there is no technological reason why that machine couldn’t be sitting right next to the automated blood pressure cuff in the drugstore.

What happens now

As Yogi Berra famously said, “it’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” Nonetheless, it’s very, very clear at this point that even without AI, information technology is able to shift the balance between the capabilities of the healthcare system and the capabilities of individual consumers.

Twenty years of over-the-counter drug switching by FDA, at least partly enabled by consumers access to information technology, has already dramatically reduced our reliance on healthcare for a variety of conditions, and reduced the number of clinicians needed by US healthcare by something like 5-10%.

As those same consumers gain access to the automated expertise that is AI, there’s no question that this process will accelerate.

Consumers can sit back and enjoy the process.

Healthcare needs to be thinking of how other organizations in other sectors — like news or travel — survived digital disruption, and pulling lessons out of those examples.

And policymakers need to be revising their predictions of “physician shortages” in light of the last thirty years of selfcare, and the promise of the next thirty.

The new Blockbuster?